All

Nurture groups: creating a safe base for learning

Across the UK, we’re seeing a dramatic spike in anxiety and absentee levels due to the impact of Covid-19 and broader socio-economic challenges. Severe absence has soared by 134% when compared to pre-pandemic levels, and more than a quarter of all children now regularly miss school. We know that 75% of children and young people who experience mental health problems aren’t getting the help they need and this makes it incredibly hard to give them the education they deserve.

But there are proven ways to tackle this crisis, and increasing numbers of schools are turning to nurture interventions to help.

Nurture groups are small groups of six to 12 children, usually based in a mainstream setting. They are designed to address the social and emotional needs that can hamper pupils’ learning by providing them with the opportunity to build resilience, understand and regulate their emotions, develop essential social skills, and engage with the curriculum. As well as providing academic teaching, nurture groups help children to develop confidence and self-respect, and to take pride in behaving well and achieving.

They are designed as a short term, part-time, focused intervention where children remain part of their own class group, and usually return full-time within four terms. The groups are based on the Six Principles of Nurture, which underpin the curriculum, context, theory and organisation of the intervention.

The inclusive and supportive nature of the group, which is led by two members of staff, helps children to feel safe and secure. The nurture staff engage with each child through a clear and predictable daily routine that includes emotional literacy sessions, news-sharing, group activities, curriculum tasks and nurture snack time.

The friendly, supportive relationship between the two members of staff is also itself an important source of learning – a model for the pupils to observe and copy. Once the children are settled into the daily routine of the nurture group, their mainstream class teacher can be invited to join the children in the room for an activity such as snack time. By doing this, pupils see the two settings as one, ensuring consistency and security for the child, encouraging positive outcomes.

Nurture groups do not work in isolation, and it is vital that all staff understand the purpose of the intervention. Senior leaders should treat the nurture group as they would any other class, with regular assessment and progress meetings. The nurture group curriculum is inclusive, often play-based, and represents activities and learning that help the pupils’ to improve skills such as speaking and listening, dealing with anger, building trusting relationships, and developing empathy.

The intervention seeks to combine the worlds of home and school for the child. Family and school are two influential systems in a child’s development and the idea that they are connected is particularly important to nurture practitioners for a joined-up approach to addressing difficulties. Nurture practitioners need to communicate openly with parents and carers so that they are fully informed about the nurture group principles and expected outcomes. As time progresses, parents and carers are invited in for sessions and activities with their child, thus building trusting relationships with parents and carers in the same way as they do with the nurture group pupils themselves.

Nurture groups provide children and young people who are struggling to access education in the classroom a safe environment to develop skills that help them be able to learn. They are just one of the interventions on the graduated approach to nurture that ensures every child has access to the support they need, when they need it.

If you’re interested in creating a nurture group for your setting, or learning more of the theory behind the approach, please visit our website. Our three-day certified Theory and Practice of Nurture Groups course equips staff with the practical skills needed to set up and run a group, whilst also providing a deeper understanding of the theory behind the intervention, and research on the developing brain and neuroscience.

The benefits of gardening for children’s wellbeing

With National Children’s Gardening Week just around the corner, it offers the perfect opportunity to introduce some gardening activities into the classroom.

Gardening brings a whole host of learning opportunities around the core curriculum subjects of science, maths and literacy. Children can learn about the world and seasons around them while gaining a greater understanding of the journey their food takes before it reaches their plates. Gardening activities can also have a significant positive impact on your students physical, mental and emotional wellbeing.

How does gardening benefit children’s wellbeing?

Getting outside and into nature gives children the opportunity to learn in a hands-on way, encouraging them to move their bodies and develop their gross and fine motor skills; for example digging, carefully separating tiny seeds and handling delicate seedlings. Gardening encourages the use of all five senses, with sight, sound, smell, touch and taste being regularly exercised, whilst sensory gardens offer a wider range of textures, visual contrasts, and fragrances. Growing vegetables offers the added benefit of the potential to expand young palettes – children are much more likely to be open to tasting foods that they have been involved in growing and nurturing themselves.

Growing plants – caring for the seeds, providing the correct growing conditions with the right balance of light and moisture, nurturing them before results are seen – requires exercising patience, resilience, persistence and commitment. Taking responsibility for helping the plant to grow, being trusted to care for it, and helping it to thrive brings feelings of pride and empowerment. Being in nature has a calming effect, and gardening has been shown to reduce stress levels, improve mood and enhance self esteem. Gardening actually makes you happy! Mycobacterium vaccae, which is found in soil, increases serotonin produced in the brain, which in turn helps to regulate anxiety.

As both a group activity, social skills are developed through team or partner work, and sharing, turn taking and respect will be required. Growing a garden offers the opportunity to advance self esteem and self motivation, and children who practise gardening at school have been shown to display increased empathy, both to the world around them and to their fellow students.

A study by Frontiers, where the behaviour of a group of 11-12 year old students was observed within the classroom and within the school garden, concluded that students showed more socially competent behaviour in school garden lessons than in classroom lessons.

How can I bring gardening into my setting?

Whilst growing a full garden can be a huge but immensely rewarding commitment, there are other ways to bring gardening activities to your setting. Gardening activities can begin inside, and if you are growing vegetables, you’ll enjoy the added benefit of being able to incorporate them into a snack time activity at a later date! Options with faster results can help to keep interest, especially for younger children.

It could be as simple as regrowing vegetables from scraps – celery, lettuce, and spring onions all regrow well and quickly when you place their bulb stem resting on top of a bowl of water.

Sunflowers, broad beans and peas are all grown from seeds and are easily germinated indoors. They can then either be sent home in cups of soil or planted into an area at school to watch them grow. Our emotional egg heads activity sheet offers another simple suggestion to start a simple gardening activity in the classroom.

Both tomatoes and strawberry plants are great fun to grow from a slice of the fruit itself – place a slice with plenty of seeds into some soil, place on a warm sunny windowsill and watch and wait for each seed to grow into a plant that could potentially produce dozens of new fruits! Both grow well in containers, or even hanging baskets, so are a great option when space is limited, and strawberries have the added benefit of coming back each year too.

If you’re able to dedicate time, space and budget for bigger projects, a vegetable patch or sensory garden are great places to start. Community requests for spare tools, outdoor clothing or seeds can prove useful for starting a gardening club or outdoor nurture space. Local garden centres, supermarkets or allotment associations are often keen to support schools in getting started.

The impact of nurturing activities like gardening can be huge for students’ social, emotional and mental wellbeing. One nurture teacher from the South-East of England recently took their nurture group to complete a two-day gardening project in a local primary school: “Every child I teach could exceed their flightpath, and that still wouldn’t come close to making me as proud as I was at the end of those two days. Each and every one flung themselves into it, working together as a team, taking turns, and supporting each other. I didn’t see a single phone or headphone all day, which with our lot is a genuine measure of success, until the end of the day when they took pictures to show their mums. There aren’t any words to adequately express how that made me feel.”

For more information on how you can bring nurturing activities and interventions into your setting, please visit our website.

Further reading:

- RHS Campaign for School Gardening

- Garden Organic school gardening resources

- Learning Through Landscapes outdoor learning ideas

- Groundwork funding opportunities

- Edina Trust funding opportunities

Supporting children and young people with anxiety

Anxiety disorders are one of the most common mental health problems, and they are thought to affect up to 19% of children and young people across the UK. They affect people both physically and emotionally, and can make children feel panicked, scared or even ashamed. Anxiety disrupts children and young people’s development, and their ability to build relationships and access education.

More and more children are arriving at school distracted and distressed – if they arrive at all. Severe absence has soared by 134% compared to pre-pandemic levels, and more than a quarter of all children now regularly miss school (Lost and Not Found report, March 2023).

Today marks the beginning of Mental Health Awareness Week run by the Mental Health Foundation, and this year’s theme is anxiety. The awareness week encourages people to share their own experiences, alongside ideas or strategies they use to manage their anxiety.

It is crucial that we provide effective support for children and young people that struggle with anxiety so that they can thrive in education and live happy, healthy lives.

Children and young people facing mental health problems such as anxiety often struggle to engage with mainstream education. They may be withdrawn and isolated, or display hugely challenging and disruptive behaviour that significantly affects those around them. Teachers need support to create safe environments that enable pupils to develop the confidence and resilience they need to succeed both academically and in life.

One of the Six Principles of Nurture is to offer a safe base. Whether this be a dedicated nurture room or mainstream classroom, the environment should be a warm and inviting space that helps children and young people to feel calm and ready to learn. It is vital for staff to be reliable and consistent in their approach to children, modelling positive relationships with each other and the children and young people.

Nurture rooms often have quiet zones or comfy areas that reflect a home. Nurture groups are designed to address children’s social and emotional needs, enabling them to better manage their anxiety. When pupils feel safe in the nurture group and in school, they are able to enjoy school more and this can have a positive impact on their school attendance.

Throughout this week, we’ll be sharing a range of advice and tips to help support children and young people to manage their anxiety. Be sure to follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or LinkedIn to access the resources to enable all children and young people to gain the education they deserve.

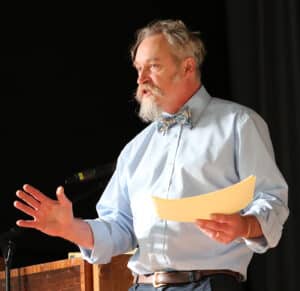

A tribute to Dominic Gubb, Senior Director of Learning at Afon Tâf High School

Afon Tâf High School in Merthyr Tydfil, Wales, is a fantastic example of how implementing a whole-school approach to nurture can support the social, emotional and mental health needs of pupils. The school is “somewhere pupils want to be”, where “staff go the extra mile with phone calls, home visits, a uniform and prom outfits bank, and even birthday presents because they know their pupils as individuals, and they want the very best for them.” (NNSA report, 2022)

Dominic Gubb, Senior Director of Learning at Afon Tâf, was instrumental in implementing the nurturing approach that led to the school achieving the National Nurturing School Award in October 2022 – a real testament to all his hard work and commitment. The award report highlighted the “unabashed level of care, love and kindness staff at all levels have for every pupil”, and the “sense of pride and belonging pupils have for their school.”

We were very saddened to hear of the sudden loss of Dominic on 15 December 2022. It is clear from the memories shared by the school and the nurtureuk consultants who worked with him, that he was a dedicated and caring educator who made a significant impact on his students and the wider school community.

Colleagues described him as a man “who made a lasting impression, he was unique. He was at Afon Tâf for 31 years, he was universally loved, respected and appreciated by our whole school community, and is dearly missed.”

Nurtureuk consultant Julie Hall worked as the assessor on Afon Tâf’s National Nurturing Schools Award application. She commented “Dominic certainly did make an impression on me with his humour, good nature and those fine whiskers. I felt welcomed as he proudly introduced me to the work of the school. On the accreditation day, I knew immediately that the team leading the NNSP had done a great job, and that Dominic very much had a personal commitment to bringing nurturing approaches to the school. He embodied nurture through his love, respect and aspirations for the young people and the community.

How sad I was then to hear of his too-early death. The other day while supporting a school with their NNSP application, I immediately brought out the Afon Tâf application to use as an example of excellence, and in describing Dominic and Afon Tâf to them, I talked about the genuine love and care shown for their pupils.”

Afon Tâf’s nurturing approach has left a lasting impression on nurtureuk staff: “These efforts, this feeling of community seems to me to be at the very heart of #TeamTaf”.

Attachment theory: why is it so important?

Our first relationship with our carers acts as a lifelong template, moulding and shaping our capacity to enter into and maintain successful subsequent relationships.

Advances in neuroscience and the development of early brain scanning have shown that feelings, empathy and emotional understanding are hard-wired into our brains through our relationships in the first years of life. So our early experiences with the people who first look after us are vital in shaping our long-term emotional wellbeing.

A safe, secure and stable relationship with a significant adult is needed to develop self-esteem and stress regulatory systems in the brain and body. They are also needed to create capacity for empathy, exploring and learning about the world around them, and fulfilling relationships later in life, as well as asking for help when troubled.

Behaviour and learning can be affected if our attachment with our primary carer(s) has been disrupted or distorted.

Secure attachment takes place when the adult is readily available, sensitive to the child’s signals, and responsive when the child seeks protection or comfort. They need to be consistent, reliable and predictable, providing a secure base for the child to explore from and return to. This will build confidence in the child that their parent/carer will be available, responsive and helpful should they encounter adverse or frightening situations.

A securely attached child learns:

- Internal models of how adults are predictable, responsive and interested in them

- Internal models of themselves as worthwhile, interesting, loveable and loved

- Exploration is safe (the child knows the adult will check on their wellbeing and safety so they don’t have to worry)

- Learning is interesting

Difficulties in the attachment process become apparent when the care-giver is not consistently available to the child or responsive to their needs. The child becomes uncertain that their needs will be met, and so begins to learn defences that give them protection from disappointment or hurt.

The insecurely attached child learns:

- Internal models of adults as unpredictable, unreliable and not interested in them

- Internal models of themselves as worthless, uninteresting and unlovable

- Exploration is not safe as the child has to look after themselves without knowing the risks

- Learning is risky as the child has not learnt through appropriate risk taking

Children who are securely attached are better able to learn and will be able to make new attachments more readily. They will be ready and willing to seek help when experiencing difficulties, both academically and socially, and will be willing to share the attention of significant adults with their peers.

By contrast, children who are insecurely attached may feel lost and unnoticed in a large and complex organisation such as school. If their internal model of themselves is of worthlessness, they may set out to prove this is the ‘right’ model each time they meet new adults, as a self-fulfilling prophecy. They may provoke unresponsive or hostile reactions in the teacher, thus reinforcing their feelings of self-doubt and insecurity.

Insecurely attached children generally require reliable adults who have time to respond to their needs, at whatever developmental stage is required. They need predictable interactions and routines, or when change is required, it needs to be explained clearly and well in advance. Clear boundaries and limitations, specific attachment figures, and adults who challenge their negative internal models through sensitive interaction are also crucial.

Nurture practice is heavily influenced by John Bowlby’s attachment theory research (1951), as well as related research by Mary Ainsworth (Ainsworth and Bell, 1970; Ainsworth et al, 1978) and Main and Solomon, 1985, which helped identify different attachment ‘styles’. The types of behaviour that pupils with social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) challenges sometimes display, such as clinging, attention seeking, panic, anger, restlessness and low self-esteem, can be understood in the context of this research.

Nurture offers a proven way to address these challenges, helping to create calmer classrooms, improve behaviour, attendance and attainment and reduce exclusions – all by supporting children’s wellbeing and ensuring they are ready and able to learn.

Recommended reading:

The trauma and attachment aware classroom – Rebecca Brooks

Nurture: what is it and why is it needed?

Children and young people are dealing with social, emotional, and mental health (SEMH) issues like never before. In the UK, the need for better support was widely recognised even before the outbreak of Covid-19, but the crisis has deepened. Cost of living pressures, compounded by the continuing impact of the pandemic, mean increased stress and anxiety for many children and families. We know that 75% of children and young people who experience mental health problems aren’t getting the help they need and this severely limits their ability to learn. Pupils facing SEMH challenges can be withdrawn and isolated, suffering in silence, others display hugely challenging and disruptive behaviour that significantly affects those around them. Exclusions and persistent absenteeism are now regular features of school life. Increasing numbers of children are arriving at school distracted and distressed, if they even make it into school at all.

So why is nurture important?

What is nurture?

Nurture is a tried and tested way of helping children develop vital social skills, confidence and self-esteem, ensuring they are able to learn. It encourages pupils to take pride in achieving – addressing the social and emotional needs that can hamper learning.

There are six principles of nurture:

Why is it needed?

We’re seeing a dramatic spike in anxiety and absenteeism levels due to the impact of the pandemic and broader socio-economic challenges. This makes it incredibly hard to give children and young people the education they need and deserve. But there are proven ways to tackle this crisis and more and more schools are turning to nurture programmes to help.

Teachers need support to create safe environments that enable all pupils to build healthy relationships, and develop the confidence and resilience they need to succeed both academically and in life. We know nurture is the way to achieve this.

“The police were always round our house – my mum was really bad on drugs at that time. My mum was never there. I was a good kid in primary school really… I started high school, and I’ll never forget, a teacher brought me and my cousin in and said “I’ve been warned about you two.” That was like a step back already, there’s already this image of me and I’ve only just started. I realised talking wasn’t doing anything so I started to live up to this name that people were giving me – “Oh you’re a fighter, you’re a badd’n.” So I started fighting and the more I fought the better I felt about myself. A few of the teachers could see I wasn’t a bad person. They took me to one side and said “What you’ve been through and your experiences in life – if you could change yourself now, it shows other kids they can do it too.” So they said to meet Michelle [the nurture teacher] and talk to her, and the way she did it was you never realised you were expressing yourself or telling your story, but you always left with a feeling of “I feel a lot better now, I’m not as angry.” It really really helped. Now I can talk to anyone and get on with anyone, but at one time I wouldn’t speak – I’d give them a stern look and leave it at that. I’m a completely different person because of nurture.” – Shane, former nurture group pupil

Nurture supports all children and young people to be able to learn, and enables teachers to identify, understand and address pupils’ social, emotional and mental health needs. A nurturing approach helps to improve attendance, behaviour and attainment, whilst creating calmer classroom environments and reducing exclusions. The outcomes can be dramatic, for children, their parents and for teachers.

At nurtureuk, we are dedicated to improving the life chances of children and young people, by promoting nurture across the whole education system and beyond. We equip educators with the proven tools they need to deliver the right support for each pupil, ensuring they are able to thrive. For more information on nurture and how you can implement it in your school, check out our range of training courses or resources.

Coronation celebration resources for nurture groups

King Charles coronation is a perfect opportunity for some interesting, creative, fun learning and we know in your settings you will be already planning exciting events to celebrate our new King.

This is a perfect opportunity to focus on many statutory curriculum links such as literacy, history, RE, art and design, geography, design and technology, music, in fact, with creativity and imagination, any subject you wish!

We have found some absolutely brilliant free resources online to share with you to help you create a fun-filled session for your pupils to celebrate and learn about King Charles III and his coronation. Included in these resources are ideas for all kinds of activities including subject-based learning and our favourite form of learning: cooking! Snack time is such an important part of the nurturing approach and in no small way contributes to the creation of trusting bonds. You can learn more about the importance of snack time in our new Snack Time Bundle. We’ve included a variety of recipes in our resource recommendations, including some from the Nurture Recipe Book which has all kinds of recipes fit for a coronation party feast!

When creating lesson plans for pupils needing a nurturing approach, it’s helpful to keep in mind the importance of developmentally appropriate practice. Whether it’s for a mainstream classroom or nurture group setting, primary or secondary, the guidance below helps practitioners to understand the needs of their pupils.

- The Boxall Profile® – using the Boxall Profile® for each of your pupils highlights their individual strengths and any difficulties that may be affecting how they learn. It can be used in a nurture group setting or for the whole class or school and gives teachers insights to know what will help their pupils engage with lessons in a meaningful way.

- The Six Principles of Nurture – a nurturing approach to teaching and learning should always take into account the Six Principles of Nurture. Here are some reminders of ways to reflect upon your approach:

Children’s learning is understood developmentally: How do you identify needs? How do you incorporate a variety of experiences in the class that meet the social and emotional needs? Consider the whole child, not just academic achievement.

The classroom offers a safe base: Consider psychologically as well as physically safe, classroom organisation, how pupils are welcomed/seated/dismissed, boundaries, rules, and routine, and fostering positive relationships.

The importance of nurture for the development of wellbeing: Are small achievements recognised? Do teachers give and maintain eye contact, using facial expressions and varying tones of voice? Knowing the child and valuing their input is key, as is the importance of social wellbeing – fostering positive peer to peer relationships.

Language as a vital means of communication: Understand the importance of early communication and language, the levels of language development, and the importance of vocabulary development at all stages and areas of the curriculum. Use emotional language to express feelings, and consider the importance of non-verbal communication such as body language, tone of voice, proximity to speaker.

All behaviour is communication: Behaviour is understood not judged – seeing the child not the behaviour. Feelings are acknowledged, and undesirable behaviour is responded to firmly but with an understanding of how this relates to underlying issues. Consider support strategies that are aimed at addressing the child’s needs.

The importance of transitions in children’s lives: How are changes in routines managed in school? Understand the significance of micro-transitions in class, and make sure children are able to talk about out of school transitions. Are bereavement, family break up or other major changes supported?

- Developmentally appropriate approaches – these are crucial to ensure each pupil is learning at their own pace and level. When we teach at their stage not age, we break down the barriers to learning and focus on things they respond to, leading to renewed confidence and engagement with learning. When looking at the resources below, consider the following points:

- Could all my pupils access this activity as it stands?

- Can I differentiate this for each of my pupils?

- How can I simplify this? (For example, short achievable steps)

- How can I make this more challenging? (Some pupils who need a nurturing approach may be academically strong and enjoy being challenged)

- What are my pupils’ strengths, how can I make sure I utilise them in this activity?

- Can I build their interests into this activity?

- Using this as inspiration, have I got any ideas like this myself which I can build into further lessons?

- How can I make this fun? (fun, laughter and joy are key for engagement with you and your lessons)

- Relationships are key – one final point for reflection is how teachers interact with pupils during lessons. The role of the key adult, and the trust and rapport that you build with your pupils is vital for opening up the world of learning to more vulnerable pupils. When trusting bonds are created, the limbic system deep within our brains responds and creates a feeling of warmth and connectivity. It can help pupils grow in confidence and self-esteem, leading to a sense of feeling safe enough to take the risk of learning something new. Always remember the most important resource in any nurturing setting is you!

We hope the resources below help engage your children and young people, and support you in your coronation lesson planning!

Resources for primary:

- Classroom display pack from Plazoom

- Royal crown craft from Twinkl

- Introduction to coronations from Westminster Abbey

- King Charles III daily newsroom pack from Twinkl

- Coronation presentations from Historic Royal Palaces

- Union Jack sensory box from The Fairy and the Frog

- King Charles III presentation from Twinkl

- Coronation crafts from Baker Ross

- Crown colouring sheet from Twinkl

Resources for secondary:

- Coronation presentations from Historic Royal Palaces

- Union Jack mason jars from It All Started With Paint

- Coronation values and symbols from Historic Royal Palaces

Resources for snack time:

- Nurture Recipe Book including flapjacks, pizza, smoothies, cakes and biscuits.

- Union Jack biscuits from The Gingerbread House

- Crown biscuits from Twinkl

- Coronation sponge cake from Baker Ross

The Boxall Profile® – A whole school approach to supporting pupil’s mental health

The Boxall Profile® is an invaluable resource for the assessment of children and young people’s social, emotional and behavioural development. It provides educators with a precise picture of a pupil’s strengths, as well as difficulties which could affect their learning. The Boxall Profile® is used by over half of UK schools that assess their pupils’ mental health.

How can the Boxall Profile® help children and young people’s social, emotional and mental health?

Children and young people facing social, emotional or mental health challenges often struggle to engage with mainstream education. They may be withdrawn and isolated, or display hugely challenging and disruptive behaviour that significantly affects those around them. One of the Six Principles of Nurture is that all behaviour is communication and so disruptive behaviour at school is a child’s way of communicating that they have unmet needs.

The Boxall Profile® is a way of understanding what lies behind pupils’ challenging behaviour to detect any unmet social, emotional and mental health needs. Once social and emotional needs are identified, education professionals can put in place targeted support to help children and young people develop those skills, and this in turn will help to improve their behaviour, mental health and wellbeing.

By using the Boxall Profile®, teachers can adopt the following strategies to help improve children and young people’s social, emotional and mental health:

- Giving pupils the opportunity to practise their social and emotional skills – for example by encouraging them to work in pairs and groups.

- Making time for social-emotional learning, either during targeted PSHE lessons or by embedding it throughout the curriculum.

- Modelling good social and emotional skills themselves, when interacting with pupils and other staff members.

The Boxall Profile® allows teachers to develop an inclusive, whole class approach that enables them to access all their pupils, by removing individual barriers to learning.

Boxall Profile® and the graduated approach to nurture

Our graduated approach to nurture ensures that every child in a school has the opportunity to flourish in their education. It ensures that every child has access to the support they need, when they need it. We work to measure and support the social, emotional and mental health of all children using the Boxall Profile®, so no child falls through the cracks.

The Boxall Profile® is an essential part of the graduated nurture approach and sits across all tiers of the nurture pyramid. The Boxall Profile® is crucial to determine what level of support the pupil needs to receive: whether the child will require access to a targeted intervention such as a nurture group, or whether other nurturing interventions such as attending a lunch time group/ afternoon club may be sufficient.

We recommend that all schools and educational settings identify the social, emotional and mental health needs of all their pupils using the Boxall Profile®, to ensure that all needs are recognised and can be supported through early interventions.

To get started or for more information about the Boxall Profile®, please take a look at our website.

Delivery begins for the Inclusive and Nurturing Schools Programme

The Inclusive and Nurturing Schools (INS) Programme, commissioned by the London Violence Reduction Unit, is now being delivered across schools in Barking and Dagenham, Islington, and Greenwich. Nurtureuk’s INS Programme Manager Jenny Perry shares her thoughts on the programme so far.

_____________________________________________________

As we begin another journey with London’s Violence Reduction unit, on the Inclusive and Nurturing Schools Programme, I have high hopes for its success. I am excited and aspirational about the impact we will have on the lives of thousands of children across London. Nurtureuk and Tender Education and Arts will be working with 70 schools across seven London boroughs to support schools in developing their knowledge, understanding and practice in the areas of inclusion and healthy relationships.

Over the last three years we have seen the huge impact that embedding a whole-school nurturing approach can have, how building policies around the Six Principles of Nurture and relationships can improve the everyday school experiences of young people and have a genuinely felt impact on their lives.

This story, told to us by one of the headteachers from a primary school on the Nurturing London VRU Programme, demonstrates the impact of a nurturing approach on a child, their teacher, the class and the whole school. It follows a young boy’s journey over nine months in the school.

“This year one pupil was experiencing physical abuse at home. In the beginning it was extremely difficult to get this anxious and angry young person into school and the classroom. With a nurturing approach, his class teacher was able to identify the emotional need behind the behaviour observed. Alongside the individual support he received from our on-site Play Therapist, his teacher was able to offer him a nurturing approach in the classroom. Trust was built by the teacher’s consistency, her ability to project a sense of calm, and by her adapting expectations and lowering task demands. This small-steps approach, along with consistent reassurance and praise slowly built the pupil’s confidence to tackle tasks and to build peer friendships independently. After four months of this approach, we started to see a much less angry young person – one who was coping, who only needed occasional reassurance and who had the ability to work with different adults. Now, almost nine months later, we have a young person who loves their school and who comes in most days. Their learning is still a level lower than age expectations, but they are willing to engage and to try.

For me, this was a case of “self-exclusion” resulting from the violence experienced at home and school feeling unsafe to a scared and vulnerable young person. I believe that our nurturing response, particularly that of the class teacher and the play therapist made the difference to this young person’s experience of school.”

The INS Programme aims to have a similar impact, by reducing exclusions and persistent absenteeism, increasing attendance and improving children and young people’s engagement and enjoyment of school. By creating a safe environment with trusted adults who listen, see and know the children and young people, and building policies and structures based on a framework of strong relationships, equity and inclusion, the programme aims to increase pupils’ sense of belonging.

The foundation of the whole-school approach is the need for evidence – to gather a clear understanding of need, whether at a school, class or pupil level. The Boxall Profile® Online helps education professionals understand the social, emotional and behavioural needs of children. With an ever growing number of pupils with identified social, emotional and mental health needs in this post-pandemic world, being able to identify those needs and support teachers to understand and manage the impact of the behaviours exhibited by these young people is only going to become more important.

Nurturing Kent Programme: 18 months on

As we reach the 18-month milestone for the Nurturing Kent Programme, we are delighted to see the level of engagement from schools across the county. To date we have had expressions of interest from around 250 schools – over 80% of our target!

The fully-funded programme has been commissioned by Kent County Council to support a minimum of 300 mainstream primary and secondary schools to develop their nurture and inclusion practices. Each school is enrolled onto core nurtureuk courses including the Theory and Practice of the Boxall Profile®, the National Nurturing Schools Programme (NNSP), and the Theory and Practice of Nurture Groups. Schools also receive a two-year subscription to the Boxall Profile® Online, credits that can be exchanged for additional consultancy support, training, online webinars and publications, and access to networking opportunities.

“We have been able to Boxall Profile® the whole school and implement strategies that are beneficially impacting whole classes. We have looked at these results and… included more nurture activities, which has resulted in the children spending curriculum time more focused and with more intent.” – Cohort 1 School

The programme is bespoke to each school, and celebrates the things schools are already doing well, whilst also identifying areas to improve and providing regular guidance and support. It ensures every child has access to an education that allows them to flourish both academically and socially.

“Children have made expected or better progress towards their individualised targets or outcomes. Their individual needs have been well supported ensuring that they are able to access the classroom and attend to tasks, have greater self-regulation and strong, trusting relationships with staff members.” – Kent School