All

Making mental health and wellbeing for all a global priority

Today is a very important awareness day, World Mental Health Day, which takes place on the 10 October every year. It is run by the Mental Health Foundation and this year’s theme is to ‘make mental health and wellbeing for all a global priority’.

It is vital that we all look after our own mental health and wellbeing, as well as supporting others with theirs. There has been a global mental health crisis since the Covid-19 pandemic, with people of all ages becoming increasingly anxious and stressed. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), there was a 25% rise in anxiety and depressive disorders during the first year of the pandemic. They also stated that there has been a severe disruption in mental health services. The need to nurture our wellbeing and prevent the escalation of more complex mental health problems has never been more apparent.

Here at nurtureuk, we are dedicated to improving the social, emotional, mental health and wellbeing of children and young people. Numerous research reports, including papers in the International Journal of Nurture in Education, have provided evidence of the positive impact that nurture principles and practices have on children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. Embedding the Six Principles of Nurture within a school environment and developing an inclusive whole-class approach enables teachers to support all their pupils by removing individual barriers to learning. This can help to make pupils feel safe at school and to be able to get on with other pupils, as well as boosting their mental health and wellbeing by developing their confidence and resilience.

There are many ways to support children and young people’s mental health and emotional wellbeing in the classroom. Some of these strategies include:

- Making time for social-emotional learning, either during targeted PSHE lessons or by embedding it throughout the curriculum.

- Giving pupils the opportunity to practice their social and emotional skills – for example by encouraging them to work in pairs and groups.

- Teachers modelling good social and emotional skills themselves, when interacting with pupils and other staff members.

- Monitoring the social-emotional wellbeing of the whole class, using assessment tools like The Boxall Profile®.

Implementing a whole-school approach to nurture is the best way to support and improve the mental health and wellbeing of all pupils and staff in a school. Our National Nurturing Schools Programme supports schools to identify children and young people who need additional, more focused support through nurturing interventions, or as part of a nurture group. Teachers can help pupils to develop the social skills they need to thrive and ensure that their needs are met. It’s vital that schools are committed to supporting all their children and young people to achieve their very best and to make their mental health and wellbeing a main priority.

This World Mental Health Day we can all play a part in helping to increase the awareness of mental health and how crucial it is to manage our own mental health and to support others with theirs. Mental health and wellbeing needs to be prioritised all around the world for people of all ages. The rise in mental disorders is a global concern, and it is only together that we can put the right support and interventions in place to help ourselves and others.

An important step in the right direction – new behaviour guidance is a welcome shift

New guidance that highlights the importance of a whole school approach to behaviour is now in force in schools in England.

The advice, published by the Department for Education (DfE), makes a welcome move away from the more punitive approach of former guidance – but does it go far enough?

Whole school approach

The guidance acknowledges that it is up to individual schools to develop their own best practice for behaviour management, but it gives a steer on how schools can and should ‘create a culture with high expectations of behaviour’. It is refreshing to see that school leaders are encouraged to take proactive steps to focus on positive behaviour. For example, the guidance suggests implementing a “behaviour curriculum” which clearly sets out what positive behaviour should look like. Staff should also have training on the behaviour policy and model the expected behaviour, and pupils should be routinely inducted and reminded of expectations, the advice says. The overarching aim of the new guidance is to create a “calm, safe and supportive environment” (a phrase emphasised repeatedly), as this limits disruption and promotes a school culture where children and young people can learn and thrive.

The guidance could go further still and recognise that behaviour policies can play an important role in fostering a nurturing environment and that a school culture needs to enable healthy social and emotional development for all pupils. For example, sections 41 to 44 of the guidance explain that responses to misbehaviour should aim to maintain the positive culture of the school and restore a calm and safe environment. There is a list of the various objectives as including: deterrence, protection and improvement. All these are important of course, but the obvious omission is the aim of supporting the social and emotional wellbeing of the pupil.

Nurturing approaches

There are a number of references to nurturing approaches – the guidance mentions “small groups” as being useful initial intervention strategies following behavioural incidents[1]. Still, nurtureuk would have liked the guidance to recognise that a nurturing approach is a central part of how schools can achieve the aim of “calm, safe and supportive environments” through behaviour policies.

The DfE consulted on the new guidance ahead of its publication. When asking which types of early intervention work best to address behaviour issues, the consultation found “many responses suggested targeted interventions to help pupils in managing their emotions and behaviour, such as mindfulness, emotion coaching, behaviour support plans, small nurture groups and support with transition from primary to secondary”[2]. It is disappointing that this emphasis is largely missing in the guidance itself.

Pupil transition and communication

It is encouraging to see the updated guidance takes into account the role of transitions on pupil behaviour. Section 10, which sets out what school behaviour policies should cover, includes – the importance of transition in children’s lives and advises that behaviour policies include detail on transitions, including the induction and re-induction into behaviour systems, rules, and routines’.[3]

Transition is one of the six principles of nurture, and it is good to see it included here. One of the other six principles: all behaviour is communication, is however not so well reflected in the guidance. A common response to the consultation regarding minimum standards of behaviour was that the guidance should recognise behaviour as both a form of communication and evidence of unmet need. It is therefore surprising that the updated guidance sidesteps this and continues instead to focus on ‘expectations’ of good behaviour.[4]

Overall, schools will find much of the updated guidance helpful in developing approaches to behaviour policy, with a whole-school approach that is consistent, inclusive and positive. There are signs here too that the new direction set by the Timpson Review, to prevent inappropriate and premature use of exclusions, is going in the right direction. However, nurtureuk would like to see future advice go further – fully reflecting the need for nurture in schools to enable all children and young people to be ready and able to learn.

[1] Behaviour in Schools – Advice for headteachers and school staff (publishing.service.gov.uk), section 96

[2] Government response to Behaviour guidance and Exclusions guidance consultation July 2022 (publishing.service.gov.uk), page 13.

[3] Behaviour in Schools – Advice for headteachers and school staff (publishing.service.gov.uk), section 10

Helping children to get Ready to Learn

The beginning of a new academic year means that children and young people will be making a transition, whether that is to a new year group or bigger moves such as Key Stage 2 to Key Stage 3 in Secondary school.

Whatever that move is, it is likely that it will involve changes in classes and teachers, possibly an increase in school size and staff numbers, different teaching styles and a broader curriculum. The social dynamics may also change and children may be faced with a more socially diverse population of young people if they are moving to Secondary Provision, for example.

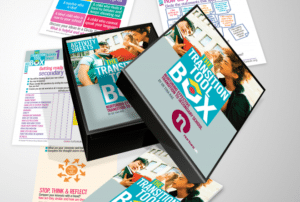

Nurtureuk’s Six Principles of Nurture tell us that these transitions can be a significant stress for some pupils and that some of our more vulnerable children will need support and additional interventions prior to any changes. Dr Tina Rae, the author of The Transition Tool Box, explains that it is important that parents and school-based staff engage in the process of promoting resilience in children and young people, in all Key Stages and particularly in the stage of transition between Key Stages 2 and 3.

Tina Rae tells us that resilience is not about invulnerability but is essentially about our capacity to cope with whatever challenges life gives us. Continuous and extreme adversity is likely to drain even the most resilient children and adults. But when children are supported in developing a positive appraisal of themselves and think differently or in a more solution-focused way about events, they are then able to feel differently about their own competence. In essence, they believe in their own ability to cope.

She goes on to tell us that resilience is not something that people either have or don’t have; resilience can be taught, and as we learn we can increase the range of strategies available to us when things get difficult. In effect, the theory of resilience provides us with an optimistic message of hope. It is indeed possible to learn resilient thinking patterns and skills that in turn help us to become more accurate and flexible in our thinking and this is important given the fact that stress and adversity are an inevitable part of our lives.

Using Tina Rae’s Transition Tool Box, we have selected some activities to support transitions before your children or pupils go back to school, to prepare them for their new routines and new environment. We will be sharing these activities across our social media platforms over the coming weeks, so be sure to follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Linkedin or Instagram. The Transition Tool Box aims to promote teaching and learning opportunities that ensure the development of resilient children and young people who can cope effectively with the process of change. The resources all aim to promote pupil participation and ensure that wellbeing is further fostered and maintained for all children and young people. Although the toolbox is predominantly aimed at Y6/7, these cards are suitable for all age groups as they can be differentiated and adapted easily, depending on age or developmental stage.

As Tina Rae explains, if all adults involved in developing programmes of support for children and young people become further aware of the importance of developing resilience and the fact that resilience can be taught and further built on then, we can further support the development of resilience and ensure that our children or pupils develop the optimism and motivation necessary to cope with life’s setbacks and changes. We hope that this resource will enable school-based staff and parents to feel empowered to more appropriately and positively support the children and young people they nurture and care for – especially during times of transition.

nurtureuk receives DfE assurance for Senior Mental Health Leads training programmes

We are delighted to announce that we are now a Department for Education (DfE) assured provider for Senior Mental Health Leads training in schools.

Our comprehensive training programmes, The National Nurturing Schools Programme and the Boxall Profile® will support Senior Mental Health Leads (SMHLs) to develop whole-school nurturing approaches to mental health and wellbeing, promoting positive outcomes for children by identifying and responding to their social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) needs.

Funding for mental health lead training has been offered to around a third of all state schools and colleges in England for the 2021-22 financial year and the Government remains committed to offering the training to all eligible schools and colleges by 2025. Schools are being encouraged to apply for a grant and can check their eligibility using the DfE guidance.

nurtureuk’s training will help SMHLs to systematically embed a culture of nurture and mental health support throughout their schools. They will be equipped with both strategic approaches and practical tools, and will be supported by a team of experts to enhance their school’s ethos and practices in a manageable and achievable way.

nurtureuk Chief Executive, Arti Sharma, said: “We’re thrilled to receive DfE assurance for our SMHL training and to be part of this vital effort to better support pupils’ mental health and wellbeing. It is essential that schools are properly supported and equipped to identify and respond to children’s SEMH needs and this funding is an important step in the right direction. We very much look forward to welcoming school staff onto our programmes later this year and helping make a real difference to the life chances of children and young people.”

Our SMHL training programmes will launch later this year. Find out more or register your interest by clicking here.

The importance of a whole school approach – welcoming new guidelines on wellbeing in education.

New guidelines on wellbeing in education have highlighted the need for a whole school approach to social, emotional and mental health (SEMH).

The guidelines have been published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and nurtureuk contributed to their creation. We are pleased with many of the recommendations, particularly the adoption of a whole school approach to support positive, social, emotional and mental wellbeing – something we are working hard to implement in schools across the UK. We believe that a nurturing approach to education is vital to improving the wellbeing of the whole school community.

Children are struggling with their social, emotional and mental health and wellbeing like never before. And those who have missed out on vital early care and relationship experiences can’t learn or function effectively. They suffer from developmental gaps and many display challenging and disruptive behaviour. Others withdraw, and struggle to engage or form relationships.

A whole school approach means that all children who require SEMH support are more likely to be identified and receive the right help at the right time. This approach ensures no child falls through the cracks and all children benefit, reaping the rewards of a more positive learning environment.

The new NICE guidelines specifically recommend that schools’ policies and procedures are consistent with relational approaches to social, emotional and mental wellbeing – a central component of nurture. The guidelines also highlight the importance of transitions, in line with one of the key principles of nurture.

The nurturing approach offers a range of opportunities for children and young people to engage with missing early nurturing experiences, giving them the social and emotional skills to do well at school and in life. At its core is a focus on wellbeing and relationships and a drive to support the growth and development of children and young people.

Our National Nurturing Schools Programme guides staff through the process of embedding a nurturing culture throughout their schools, enhancing teaching and learning, and improving outcomes for children. The programme includes access to The Boxall Profile®, nurtureuk’s unique assessment tool which enables teachers to develop a precise and accurate understanding of children’s social and emotional competencies and behavioural needs and skills, and plan effective interventions and support.

Every child should be given the same opportunities to lay the foundations for a rewarding adulthood. We hope to see all schools commit to these new guidelines and crucially, we want to see long-term government investment in nurturing approaches in schools in order to transform the lives of vulnerable children and give them the best chance to thrive.

Applying the Six Principles of Nurture

This blog has been written by Ciaran Thapar, author of Cut Short: Why We’re Failing Our Youth — and How to Fix It.

As a youth worker and writing coach, working mostly with young people who find themselves easily excluded from mainstream experiences of British society, discovering the six nurture principles over the last year has been game-changing.

Across 2015-2021, I worked for various charities in a range of settings — secondary schools, youth clubs, prisons — where I supported young people with their academic pursuits and provided safe group and 1-to-1 discussion spaces for boys and young men at-risk of serious youth violence. My book, Cut Short, documents much of this work, focusing on the experiences of three young men I worked with (Jhemar, Demetri and Carl) as they navigate through, and triumphantly overcome, the barriers of systemic inner-city inequality. In 2021, following publication, I started thinking about how to merge my youth work practice with my love for writing as an expression-of-self and medium for self-reflection. Around this time, I was contacted by nurtureuk to collaborate on some work, following their reading of Cut Short, and this birthed PATTERN, a writing course for boys and young men at-risk of permanent school exclusion.

I have therefore been on a journey of finding my deeper purpose as a youth worker, while absorbing the principles of nurture into my thinking. The following are some ways in which I have applied them to my practice, and examples of where they can be drawn from the journeys of the characters in Cut Short.

Children’s learning is understood developmentally.

Life circumstances are impossible to control completely, especially if you are a child. This means there is a constant mesh of forces playing into a young person’s experience of life, and therefore their ability to engage in learning, formally or informally. Understanding that education can only be achieved when the learner is given the space to absorb the learnings sounds like an obvious principle, but it is constantly disregarded in the British school system. Those who are able to tick the narrow boxes of high pressure examinations are rewarded; those who are unable to do this become less of a priority. One obvious signal of this is the way that the arts have been dismantled and devalued in recent years, giving way to obsessions with core subjects. Many of the smartest young people I’ve worked with were not able to excel in academic subjects. Their intelligence could shine in safe conversational settings, or in the poetic lyricism of their raps, or in their mature ability to analyse their complex social worlds, none of which is readily appreciated on paper. The fundamental differences between Jhemar, Demetri and Carl is a case-in-point: they are written into Cut Short to demonstrate three diverging blueprints of success, despite all the obstacles that London throws at them, be that academic, social, artistic or athletic. Respect must be paid to the individual and their circumstances in any process of learning.

The classroom offers a safe base.

Too often, in the rush of the timetabled day, it is missed that school regimes can provide safety and comfort to the most vulnerable students. For many boys I’ve worked with, as soon as they step foot outside the school gates, they perceive their life to be in danger. This means that the sanctity of the classroom needs constantly reinforcing. The problem is that, in many cases, this logic is turned on its head: the classroom becomes a place of punishment and shame. In Cut Short, Carl is sent to the exclusion room to sit on his own and face the wall. He is ignored or dismissed by teachers when he tries to speak to them; the more he gets sent to the exclusion room, the more some members of staff treat him automatically as a problem to get rid of, rather than to treat with greater empathy. I have seen this play out during my own time working in schools, and it extends to the way that police, prosecutors, and the wider public can respond to the most socially excluded young people. It is vital that the classroom – and school space in general – is seen as an opportunity to give young people like Carl the chance to unwind, open up about their experiences, and be vulnerable, without the constant fear of punishment or harm. This is the idea behind PATTERN: to provide a regular pattern in students’ lives where they can sit at a desk, discuss social issues and write their ideas down in a way that is valued by relatable mentors.

Nurture is important for the development of self-esteem.

The most important tenet of any youth work I do, and the core message of Cut Short, is to make young people feel like they are valued. If a young person is granted space, support and time to grow, make and learn from their mistakes and develop, and the positive aspects of their journey are reinforced by adults, the strongest foundation for life can be built. One of the main reasons that Jhemar was able to cope with family tragedy, and resist the urge to take justice into his own hands, was the deep knowledge that he mattered to adults around him, his friends and his community. He knew he needed to rewrite the script, because it had been communicated to him that he was powerful enough to do so. Carl was able to halt a cycle of crime and violence, despite the extreme dysfunctionality of his home life, and the risk of being attacked or policed, because he had a range of trusted adults around him to confide in and discuss options for his future with. Nurture ensured these two very different young men were able to develop and hold onto a strong sense of self-esteem. This is what saved their lives, and both are now able to move with confidence and give back to their communities tenfold as a result.

Language is understood as a vital means of communication.

Slang should not be punished, only challenged and collaborated with, for it exists as an adaptation for life on the fringes. Rap music should not be policed, it should be harnessed as a tool of expression, learning and catharsis. Converting the thoughts and mutterings of groups of young people into written words that can be published and handed out to their communities is a deceptively powerful step. Language is so powerful, and can say so much, yet the outbursts of children and young people are often ignored. In our PATTERN writing workshops, every contribution is valued and digested, and each participant is encouraged to write their honest thoughts down in order to understand them better, and place them in a wider social context. Increasingly, rap lyrics are being used in court as evidence to convict young people who write them. There is nothing more symbolic of how British society silences and demeans young people who face adverse life experiences. Throughout Cut Short, I try to show the vitality of music culture, literature and language more broadly as key media for understanding, supporting and communicating with young people.

All behaviour is communication.

When Carl failed to show up to mentoring sessions at his youth club, despite the fact we’d known one another for over two years, I was advised by Tony, my mentor, that he was testing the boundaries of our relationship. By continuing to show up, messaging him each time to signal that I was there when he needed me to be, and letting him come when he was ready, formed an effective communication between youth worker and young person. Working with young people can be frustrating because their behaviour can be testing, but a trauma-informed practice sees this as a product of forces outside of the room, stemming from the past. Receiving behaviour as communication is a great way of sustaining a dialogue with a young person, because it necessarily demands a response – rather than a reaction – and a careful, supportive response can make all the difference. I enjoy working with young people whose behaviour is regarded as poor in classroom settings most because they communicate honestly and aren’t afraid to challenge the structures placed upon their lives. This spirit can be channelled in the most amazing way.

Transitions are significant in the lives of children.

Year 6 to Year 7; school to college; college to university. Moving home (once, or more than once), the coming and going of parents or carers, the turnover of teachers and youth workers. These are all transitions that, if not managed properly, can have an unpredictable and often quite invisible impact on a young person’s life. I’ve learned the hard way — as I show at different points in Cut Short — that my own lack of consistency in certain roles I’ve played meant that I couldn’t forge strong, long-term relationships with staff or young people. I’ve tried to learn from these mistakes and ensure that wherever I deliver youth work there is a sense of beginning, middle and end; some control of structure and closure. But this is only possible when institutions are managed properly and empathetically, and when the wellbeing of staff is ensured, thus making their roles sustainable, which isn’t always possible in cash-strapped schools, youth services or prisons. The most impactful youth work I’ve done, and seen done by others, is that which takes places over the long-term, at multiple moments of transition. Change can be destabilising, but it is also where we learn.

Ciaran’s book Cut Short is now available to purchase in paperback: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/316628/cut-short-by-thapar-ciaran/9780241988701

The importance of nurture for LGBTQ+ young people

All children and young people deserve the opportunity to flourish, both in the classroom and beyond. They should have access to the support they need, when they need it, and no child should fall through the cracks.

This Pride Month, we want to highlight how nurture approaches can support children and young people questioning their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. The six principles of nurture are crucial for creating a safe and respectful environment with trusted adults, where all young people can access the support they need.

Research from the University of Cambridge found that over half of lesbian, gay, bi and trans (LGBT*) young people did not feel there was an adult at school or college that they could talk to about being LGBT*, and 60% did not have an adult they could talk to at home. Nearly half (45%) of LGBT* young people – including 64% of trans young people – were bullied at school or college for being LGBT*.

At nurtureuk, we equip and support adults working with or caring for children and young people with evidence-based tools to help them flourish inside and outside of school. We believe that a child’s learning needs to be understood developmentally, and we want to amplify the benefits of nurture for children and young people both within and beyond the classroom. Everything we do is guided by the six principles of nurture.

A nurturing approach benefits all children, including those who are LGBTQ+ or exploring their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Ryan Gingell-Scott from the charity Allsorts Youth Project, is applying his nurtureuk training and the six principles of nurture to his work with children and young people who are exploring some of these questions.

The classroom offers a safe base

A safe environment is foundational for children and young people to feel calm and welcomed. As well as providing a physical safe space, a ‘safe base’ can also be a person: “The secure base [can be] provided through a close relationship with one or more sensitive and responsive attachment figures who meet the child’s needs and to whom the child can turn as a safe haven when upset or anxious… When children develop trust in the availability and reliability of this relationship, their anxiety is reduced and they can therefore explore and enjoy their world independently, safe in the knowledge that they can return to their secure base for help if required.” (International Journal of Nurture in Education, Vol. 6, p36)

For Ryan’s work, offering both a physical safe space and a secure person is vital: “Working out who they are, in a safe, respectful and nurturing environment is key to giving them the solid foundations to build upon as they grow up… we provide a place to create those secure attachments and positive relationships with safe adults. This development matters and impacts their journey into being happy, healthy young people who thrive as they grow up.”

All behaviour is communication

In addition to the immediate community of friends and family, children and young people are also embedded in wider communities that may affect their experiences. These communities could be a range of educational settings, sport, faith, youth organisations or statutory services. Their behaviour may be a product of one or more of these areas of their life and it is important to take the time to understand the entire world around the child to understand what their behaviour is communicating.

“For many of the young people we see, behaviour has been the only way they can communicate their sense of self up until this point. At times the behaviour is showing anger, fear or upset and we need to work out the driver for the behaviour, and explore this alongside them to unpick what they are telling us,” highlights Ryan.

Language is a vital means of communication

Supporting children and young people to develop their language enables them to communicate their experiences more effectively both in the short and long term. Ryan’s work includes “…developing their language skills as we know this is a vital means of communication. We use activities to help give language to their emotions, to help them recognise, regulate and manage their feelings in a way which is safe. By ensuring we implement the principle of language being a vital means of communication, we are giving them the tools they need to advocate for themselves as they grow up.”

The importance of transitions in children’s lives

Whilst all children experience transitions throughout their lives, the nuances, challenges and complexities associated with these moments for LGBTQ+ children and young people cannot be understated.

Ryan explains, “As much as possible, we plan for these moments and try to limit the stress, anxiety and fear that usually runs alongside such big steps. Our job is to help children communicate these fears and anxieties so that the intensity of transitions, such as moving to secondary school, is minimised.”

The importance of nurture for the development of wellbeing

For Ryan, the importance of nurture for the development of wellbeing is threaded through everything he does: “We can prepare the children for what is to come and help them establish healthy relationships, set boundaries and clearly communicate their feelings in healthy and safe ways, which in turn makes these big life transitions easier to manage.”

He concludes: “Implementing the nurture principles as early as possible with the children we work with helps them to understand they are deserving of a voice and that it is okay to be themselves, regardless of whether this is long term or just for now. These children are brave, inspiring and full of life…and they deserve nurture now more than ever.”

*Report published prior to updated more inclusive terminology – Lesbian, gay, bi, trans and queer/questioning (LGBTQ+)

Why we should encourage children to start gardening

It is National Children’s Gardening Week, an opportunity to celebrate the fun of gardening for children. It is a great activity for children to enjoy outside in the fresh air that provides a range of additional health benefits.

National Children’s Gardening Week was started by Neil Grant, Managing Director of Ferndale Garden Centre, and one of BBC Radio Sheffield’s garden experts. The awareness week has become an annual festival and it is widely supported by the whole of the UK garden industry.

Gardening is a fun, educational activity where children can learn about the different species of plants and how together we can help them to grow. Children get to learn about the different seasons and weather conditions that may affect plants. It also gives children the chance to find out more about the wide array of animals and insects that live in gardens, and is an excellent activity for children to take part in either at home or at school.

There are many benefits associated with gardening. It can be a very sociable activity, especially in schools. Children can work as a team and it gives them the opportunity to bond with their peers and teachers, as they help to nurture each other as well as nurturing their own flowers. Gardening is a recommended activity in nurture groups because of the positive impact it has on developing children’s social skills. This is especially important for pupils who have social, emotional and mental health difficulties that make it harder for them to learn in a mainstream classroom.

“Nothing comes close to making me as proud as I was watching my nurture group gardening. Each and every one flung themselves into it, they worked together as a team, turn taking and supporting each other. I didn’t see a single phone or headphone all day – which with our lot is a genuine measure of success – until the end when they took pictures to show their mums!” – KS4 Nurture Group Teacher

Gardening also helps children with their sensory development. It can engage a variety of different senses which helps children to recognise and develop them. For example, they can feel the texture of the soil and petals, along with smelling the wonderful scents from all of the flowers. In addition, gardening builds up children’s physical strength as well as developing their hand-eye coordination.

With less children heading outside these days due to TV and other technology, it is vital that we do all we can to reconnect them with the beauty of nature. The lessons that children learn from gardening reap fantastic rewards. By encouraging children to start gardening early, it’s more likely that it will continue to be a hobby for them for life.

The impact of nurture for those ‘on the fringes’

We know that a nurturing approach can have an incredible effect on the lives of children and young people, and we love to hear about the real-life impact it has in the schools we work with. The following case study is from a school on our Violence Reduction Unit Programme.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

I stumbled into the academic year with low expectations of doing anything other than closing Covid gaps, tackling mental health issues and making a saddening number of referrals to Social Services. Then, I accidentally joined a network meeting of professionals working to reduce serious youth violence in my area; a spark was lit.

These virtual monthly meetings gave me insight into what was happening with young people in my area, and I started to make connections with people and services I’d never heard of before. I was plodding along in my role feeling more informed and able to support some of our most vulnerable. But feeling that way is never really enough, is it?

I shared my learning with colleagues and we took part in county lines training; we started to bang the same drum and our voices were being heard. But I was still frustrated that the best I could offer families was a referral for support (often declined), a listening ear for parents, and a walk around the field with students venting about how they were facing another exclusion. Knowing our stuff was one thing, but listening to a child tell us he smoked weed because ‘what else is there to do in this town, Miss?’ made me feel impotent and so very sad.

That was until one of my partners at the Serious Youth Violence Team asked me if I had heard of nurtureuk.

It was one of those moments where things somehow all came together at the perfect time; a fully-funded place had come up for a school in my area on nurtureuk’s project with the Violence Reduction Unit. The programme worked with schools where the cohort were at risk of exploitation, involved in the criminal system, and had high disengagement.

The spark that was lit before now had petrol liberally poured all over it. I was desperate to be part of the project, and several pleading emails to our leadership later, we were in.

Every training session I attended gave me ideas and inspiration. I knew our kids, I knew how adverse their backgrounds were and I knew this would make a difference for them. Our team started attending every available training session, and our pastoral team who have been fighting fires for years, finally saw something we felt could help our families.

We started to roll out information to staff ready to introduce the nurture principles in the new academic year. So many of our staff were naturally nurturing and had excellent relationships with our children. We were already doing so much of what we had learned, but the programme gave us structure and a clear path forward to become a whole nurturing school, not just one where most staff nurture through the nature of their personalities.

However, this did nothing for those already on the fringes. I hated to think what would happen to them. For two of them, Young Offenders’ Institution was looking likely before the end of the academic year. Some of these children had been under my pastoral care since Year 7 and were now in Year 10; I knew their parents, and spoke to them more than my own parents most weeks. I knew their Early Help workers, their drug and alcohol abuse workers and what they were scared of. I also knew I couldn’t offer them anything better than those who had them carrying out retribution fights and running drugs could offer them. Why would they trust us? We had excluded their friends or sent them elsewhere as we could no longer manage them in school. They were angry, defiant, violent, lost; and I wanted to save them all. I felt that hopeless feeling creeping in again, like I had all the ideas but I had missed my chance.

During the nurture training, we learned about the concept of nurture groups. I presented them as a wildcard proposal to our leadership team – I wanted to completely rebrand our current alternative provision and use it as a Key Stage 4 nurture group. I suggested changing our current internal exclusion provision from a punitive cubicle nightmare that David Brent would have been proud of, into a transient nurture room. I didn’t hold out high hopes, I just wanted recognition that the need I was raising was also seen by others, and that maybe it would be considered for post-Covid world with new priorities. Two days later I got called to the Head’s office where I was offered everything I’d asked for and more.

The first thing I did was complete a Boxall Profile® for ‘Boy A’. He was the first child that made me recognise the impact that having just one person in your corner could do for you. He came to me in Year 7 labelled “naughty with difficult parents”, and by Year 10 he had an EHCP for his severe learning needs, which he had masked by being popular, and I had an incredible relationship with his parents. He was facing exclusion for his defiance and violent behaviour, and was far too well known to the police. Having taught this boy too, I had no rose tinted glasses on when it came to his behaviour! I completed his Boxall Profile® and cried when I read his results. I wanted him in my new provision, and he joined the following week.

I was keen to quickly show that the best way to engage with our most challenging young people was to nurture them. I was granted permission to take my new nurture group and three others with a similar reputation off site for a two day gardening project at our local primary school.

Every child I teach could exceed their flightpath, and that still wouldn’t come close to making me as proud as I was at the end of those two days. Each and every one flung themselves into it, working together as a team, taking turns, and supporting each other. I didn’t see a single phone or headphone all day, which with our lot is a genuine measure of success, until the end of the day when they took pictures to show their mums. There aren’t any words to adequately express how that made me feel.

Mr X, one of our naturally nurturing teachers that our most challenging young people adore, and I worked alongside them; sometimes quietly, sometimes putting the world to rights with them. One boy, who had the highest rate for exits from lessons in his year, told me that all plants have faces and how I should plant them. The solitary girl of the group, who had always been very reserved as she worked through her own issues with ADHD medication and the grief of losing family members, spent the break chatting with all the boys for the first time.

As we packed away, all the young people thanked us individually. The parents emailed us to thank us. The primary school children came out and our young people glowed with pride showing off their flowers. I glowed watching them. I could tell this was the start of something wonderful.

I sent an email to staff bragging about how amazing my team of ‘delinquents’ were; a part of me wanted to show some of their teachers they were wrong. These young people were brilliant, wonderful, and misunderstood. I have since heard staff telling them they have heard all about their good work and praising them, which for this group is a huge deal.

So what’s next?

We gathered serious momentum in such a short space of time. The new academic year looms and I can’t wait to see what it holds. We weighed up the benefits of getting a class rat – they hated the idea. We discussed how they will paint their new classroom, and what project they would like next (bird boxes got the final vote). We spoke about how we can support them in moving away from their gang outside of school (“Miss, we’re a group not a gang, police can’t get you for being in a group”). I have a huge sheet of paper with plans, and an extremely supportive leadership team allowing us almost free reign to meet these needs as we see fit.

Our next challenge is convincing all staff that yes, we can offer tea and talking to students rather than silent working and a pound of flesh for misbehaviour. We need them to see behaviour as communication, not just a nuisance. We need to plan how to ensure Ofsted will like what we do, and that we are still measuring successes each term. We need to work out how we will have subject specialists work with the children still. I need to work out how my boy with an enforced ankle bracelet will join us for off site activities.

It will no doubt be challenging, but for the first time I feel I am at the start of being able to actually do something to help them, and it’s so exciting. We planted our own seeds, we’ve started the watering process, and I can’t wait to see them bloom.

Tackling loneliness by building nurturing connections

Today marks the start of Mental Health Awareness Week, and this year aims to highlight the impact of loneliness.

Research from the Mental Health Foundation found that loneliness affects millions in the UK every year, and is a key driver of poor mental health. A 2018 report from the ONS found that 45% of children aged 10-15 felt lonely ‘often’ or ‘some of the time’. This stark statistic exposes the problem of loneliness in children and young people, even prior to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Barnardo’s identified in their 2020 report the need to develop relationship-based programmes that support children to rebuild connections that were disrupted as a result of isolation during the pandemic. This key recommendation can be implemented through nurturing approaches that focus on relationships and connection.

“A nurturing approach recognises that positive relationships are central to both learning and wellbeing. It recognises that all school staff have a role to play in establishing the positive relationships that are required to promote healthy social and emotional development… A nurturing approach has a key focus on the school environment [incorporating] attunement, warmth and connection…” – Education Scotland, Applying Nurture as a Whole School Approach

Loneliness in children can be expressed in many different ways, including “disguised expressions of anger, or physical distance from the teacher” (IJNE, Vol. 2, p17). We know that all behaviour is communication, and schools have a vital role to play in understanding these behaviours, and building connections with children and young people.

The nurturing approach offers a safe base for children struggling with loneliness to build positive relationships and connections, both with their peers and their teachers. Nurturing interventions, including the whole-school approach, focus on emotional wellbeing for all pupils, and help them to develop social and emotional skills, and develop resilience.

This week, we will spend time highlighting the issue of loneliness amongst children and young people, and discussing how nurturing approaches can be used to help build positive connections and relationships. Be sure to follow us on social media for advice and resources on building meaningful connections with children and young people, or for more information on implementing nurture interventions in your school, please visit our website.